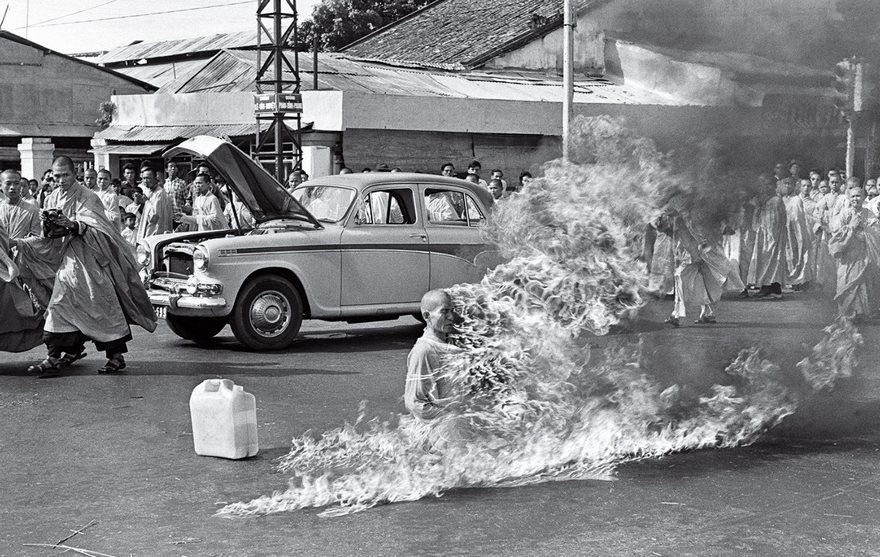

#2 The Burning Monk , Malcolm Brown, 1963

In June 1963, most Americans couldn’t find Vietnam on a map. But there was no forgetting that war-torn Southeast Asian nation after Associated Press photographer Malcolm Browne captured the image of Thich Quang Duc immolating himself on a Saigon street. Browne had been given a heads-up that something was going to happen to protest the treatment of Buddhists by the regime of President Ngo Dinh Diem. Once there he watched as two monks doused the seated elderly man with gasoline. “I realized at that moment exactly what was happening, and began to take pictures a few seconds apart,” he wrote soon after. His Pulitzer Prize–winning photo of the seemingly serene monk sitting lotus style as he is enveloped in flames became the first iconic image to emerge from a quagmire that would soon pull in America. Quang Duc’s act of martyrdom became a sign of the volatility of his nation, and President Kennedy later commented, “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.” Browne’s photo forced people to question the U.S.’s association with Diem’s government, and soon resulted in the Administration’s decision not to interfere with a coup that November.

#8 Earthrise, William Anders, NASA, 1968

It’s never easy to identify the moment a hinge turns in history. When it comes to humanity’s first true grasp of the beauty, fragility and loneliness of our world, however, we know the precise instant. It was on December 24, 1968, exactly 75 hours, 48 minutes and 41 seconds after the Apollo 8 spacecraft lifted off from Cape Canaveral en route to becoming the first manned mission to orbit the moon. Astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders entered lunar orbit on Christmas Eve of what had been a bloody, war-torn year for America. At the beginning of the fourth of 10 orbits, their spacecraft was emerging from the far side of the moon when a view of the blue-white planet filled one of the hatch windows. “Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!” Anders exclaimed. He snapped a picture—in black and white. Lovell scrambled to find a color canister. “Well, I think we missed it,” Anders said. Lovell looked through windows three and four. “Hey, I got it right here!” he exclaimed. A weightless Anders shot to where Lovell was floating and fired his Hasselblad. “You got it?” Lovell asked. “Yep,” Anders answered. The image—our first full-color view of our planet from off of it—helped to launch the environmental movement. And, just as important, it helped human beings recognize that in a cold and punishing cosmos, we’ve got it pretty good.

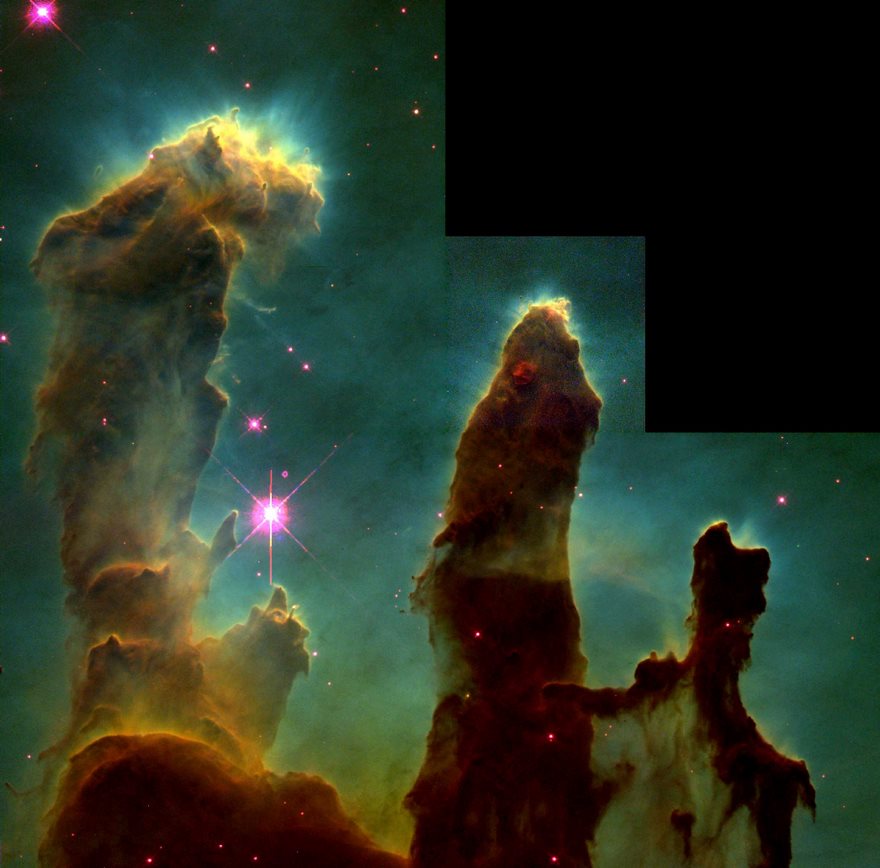

#11 Pillars Of Creation, NASA, 1995

The Hubble Space Telescope almost didn’t make it. Carried aloft in 1990 aboard the space shuttle Atlantis, it was over-budget, years behind schedule and, when it finally reached orbit, nearsighted, its 8-foot mirror distorted as a result of a manufacturing flaw. It would not be until 1993 that a repair mission would bring Hubble online. Finally, on April 1, 1995, the telescope delivered the goods, capturing an image of the universe so clear and deep that it has come to be known as Pillars of Creation. What Hubble photographed is the Eagle Nebula, a star-forming patch of space 6,500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Serpens Cauda. The great smokestacks are vast clouds of interstellar dust, shaped by the high-energy winds blowing out from nearby stars (the black portion in the top right is from the magnification of one of Hubble’s four cameras). But the science of the pillars has been the lesser part of their significance. Both the oddness and the enormousness of the formation—the pillars are 5 light-years, or 30 trillion miles, long—awed, thrilled and humbled in equal measure. One image achieved what a thousand astronomy symposia never could.